Specific treatment for musculoskeletal pain can be complex but a systematic approach works

There are seemingly an untold variety of assessment and treatment methods for musculoskeletal pain. How do we develop our foundation skills and select new innovative methods to learn?

The STOPS.physio team work on the following principles:

If there is high quality evidence to support a treatment you should strongly consider it for most patients

Always consider randomised controlled trial level evidence but don't forget other research designs (eg studies on mechanisms) which provide equally important information that informs clinical practice

An absence of evidence does not mean a treatment approach should be abandoned; for this to occur a treatment needs to be proven to be ineffective in a clinical trial

Where ever possible look to experts to synthesise the evidence (eg systematic reviews). Be wary of reviews that do not take into account the clinical perspective or make didactic recommendations with insufficient high quality supportive evidence

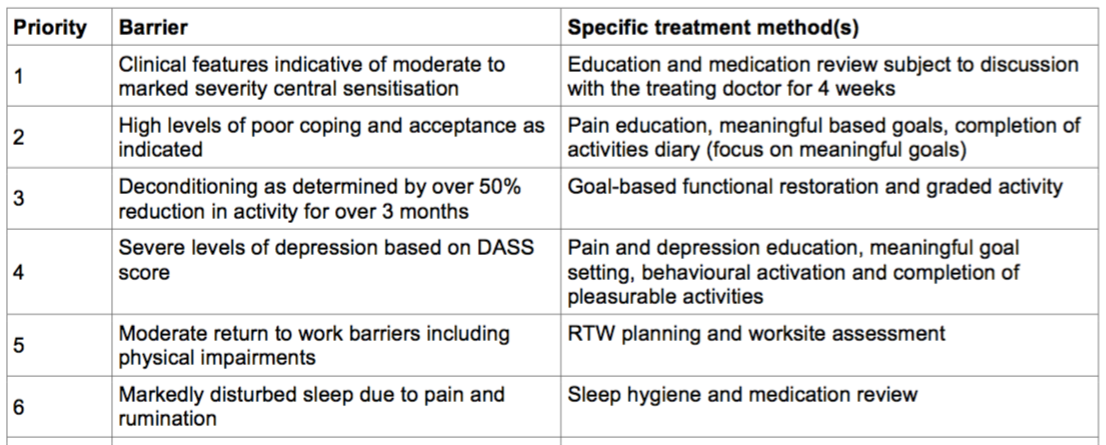

Below are some examples of how specific treatment can be implemented based on the above principles. Further information is also available from the STOPS.physio summary for back pain and the detailed treatment protocols available in full text. A range of other clinical tools and papers are also available on the Resources page.

The importance of assessment in back pain

The World Health Organisation's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) recommends comprehensive assessment of all factors relevant to a health condition. Using low back pain as an example, a thorough assessment should always include:

A detailed history (eg recent and past symptoms, work, sport/recreation)

Body chart including severity, irritability and nature of symptoms

Aggravating and easing factors

24 hour behaviour including morning, end of the day and night symptoms

Special questions (eg imaging, medication, general health)

Observation (eg posture, gait, functional testing/modification/retesting)

Active movement testing

Neurological examination (as required)

Provocative neurodynamic testing (as required)

Palpation including passive accessory intervertebral movements

Passive physiological intervertebral movements

Motor control including deep/local muscle function (eg transversus abdominis)

Special diagnostic tests such McKenzie repeated movements or provocative sacro-iliac joint tests

Determination of neurophysiological pain mechanism (eg central sensitisation)

Musculoskeletal screen including items such as muscle length/strength

Functional outcome measures such as the Oswestry

Screening questionnaires such as the Örebro/DASS for psychosocial risk factors

Not every patient requires a full assessment but physiotherapists should have the interviewing, practical and clinical reasoning skills to complete the above, particularly in cases of persistent pain. A full assessment will allow determination of barriers to recovery such as those described below. This then drives effective specific treatment.

Central sensitisation

With good reason there has been an explosion of information on musculoskeletal pain and the role of the sensitised nervous system. There is no doubt that practitioners need to assess and treat central sensitisation in certain patients. However some caution is also required. There are no diagnostic gold standards for central sensitisation and inexperienced practitioners can over diagnose this barrier to recovery in patients who may have an important nociceptive pain mechanism. The STOPS.physio team believe the best method for diagnosing pain mechanisms was described in an expert panel study by Dublin physiotherapist Keith Smart (available in full text). By carefully evaluating these criteria practitioners can tease out the likelihood of the patient having a nociceptive, neuropathic or central sensitisation pain mechanism (or a combination thereof). Specific treatment along the lines of our STOPS trial protocols can then be provided.

controversy around pathoanatomy

Most practitioners are aware that there is little correlation between imaging findings and symptoms. So for every 100 people without back pain at least 50-60% of them will have some sort of "structural anomaly" like a disc bulge on CT or MRI scan. However this fact alone does not mean that pathoanatomy is irrelevant to clinical decision making (as some attest). "False positive" findings are not unique to imaging. Consider the high prevalence of mood issues in the community in people with and without musculoskeletal pain. And as discussed above we are not even sure we can accurately diagnose central sensitisation. So based on current research we cannot be sure on the false positive rate in people with psychosocial and neurophysiological barriers to recovery.

In addition, pathoanatomy can be very important in some patients, even those with persistent pain. A common presentation seen in our multi-disciplinary pain management clinic is patients with repeated knee surgery whose leg gives way frequently during weight bearing. Despite whatever psychosocial or neurophysiological barriers are present, our priority is always for the patient to regain functional knee control either through specific muscle retraining and strength work and/or range restricting custom knee bracing. Such patients when provided with treatment to restore control of their knee dramatically improve.

The STOPS.physio team published a paper exploring some of the misconceptions around the relevance of pathonatomy which is available in full text.

Towards an understanding of mood issues

Most practitioners understand that mood can have a negative impact on pain perception and also prognosis for recovery. However it doesn't necessary follow that all patients with low mood will do poorly. Some patients may have depression or anxiety that is completely unrelated to their musculoskeletal pain problem. Again thorough assessment and clinical reasoning skills can help tease this barrier out. Screening questionnaires like the Örebro are useful for identifying possible barriers to recovery. But to more completely evaluate mood issues the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 is much more valid and clinically useful. The full questionnaire and scoring method are available and practitioners suspecting serious mood issues should avail themselves of this resource. A conversation with a patient's GP is the minimum requirement if severe or extremely severe depression is noted. Extremely severe anxiety is also of concern despite some forms of pain related anxiety being possible to treat by physiotherapists.

lets talk about bob

The following case study of Bob illustrates the principles of specific physiotherapy.

Bob is 45 years old and has a history of episodic back pain due to his work as a carpenter. Eight months ago he suffered a sudden onset of severe central low lumbar pain due to lifting 20kg at the end of an extra long day at work. Hands on physiotherapy makes the pain worse for a day or so and he cannot return to work. Bob finds any position uncomfortable after 20 minutes. He only gets 4 hours sleep due to pain and rumination. Examination shows Bob is moderately restricted by pain in all directions and his Örebro score is 150/210 suggesting a high risk of poor outcome.

Consider for a minute what barriers to recovery might be relevant...

Bob's assessment is not complete but based on the information we have it is plausible and possible that he has discogenic pain based on the history (mechanism of injury, past history). There are likely to be significant psychosocial factors (based on being off work, the persistency and the Örebro scores) and central sensitisation is also a consideration (high severity, sleep issues, non-directional specific agg factors). However if Bob has discogenic pain it is plausible that inflammation is a factor that does not appear to have been treated. On this basis a prioritised list of barriers to recovery and associated individualised treatment might be:

Inflammatory discogenic pain - treat aggressively with NSAIDs, tape, postural modification, gentle non-provocative activity (walking), advice

Motor control retraining (transversus abdominis, pelvic floor, lumbar multifidus) to increase dynamic stiffness for the lumbar spine and disc during function

Reassessment of extension in lying (and other McKenzie based mechanical loading strategies if inflammatory based treatment is successful)

Further assessment (eg specific questionnaires) and close monitoring of psychological distress and features of central sensitisation to evaluate cause/effect relationship. Be prepared to change approach if treating pathoanatomy is unsuccessful

Workplace intervention to facilitate sustainable return to work given the multifactorial benefits provided it is suitable duties and hours

This case illustrates the importance of clinical reasoning in identifying barriers to recovery and prioritising treatment. Continual assessment, treatment and reassessment is essential to gain an evolving understanding of the patient problem. The case also shows that when all factors are considered pathoanatomy can be managed in a clinical model that also considers impairment, psychosocial and neurophysiological factors. Importantly the case is a very simple and common presentation. In the context of a full assessment, the identification of a prioritised list of barriers and the application of specific treatment is significantly more complex.